Maths & Oceans #3: Mathematical modeling of marine biodiversity

What mathematical methods and tools can be used to understand marine ecosystems? How can underwater data be analyzed? An article by Jean-Christophe Poggiale, lecturer and researcher at the Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO)1 .

- 1UMR7294 / CNRS / Aix Marseille Université

The links between mathematics and marine biodiversity are more numerous and more frequent than one might imagine at first glance. The aim of this article is to give two examples: the role of biodiversity in the functioning of the oceans and biodiversity as an exploited resource.

Marine biodiversity often conjures up images of colorful ecosystems inhabited by brightly colored organisms moving through a silent world. In reality, the biomass living in the oceans also takes the form of microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria, and plankton cells, and it is these life forms, invisible to the naked eye, that make up the bulk of ocean biodiversity.

Although microscopic, these species are so numerous that they contribute significantly to the conditions of our life on Earth. For example, phytoplankton consumes carbon dioxide (CO2) and produces oxygen (O2). These two functions play a major role in regulating the climate and supplying oxygen to the atmosphere. Phytoplankton and bacterioplankton are therefore essential players in what is now known as the biological carbon pump, which helps slow down global warming. In general, understanding how marine biodiversity works is an important challenge for oceanographic research. These ecosystems are difficult to access and observe directly, so mathematics is an indispensable tool for exploration.

In this context, the scientific study of biodiversity involves not only monitoring the number and density of emblematic species, but above all understanding how marine species coexist and under what conditions this diversity enables marine ecosystems to function and endure.

To understand how marine ecosystems function and what role biodiversity plays in them, mathematics offers a set of indispensable and fruitful methods and tools: dynamic systems theory, in particular, makes it possible to extract information contained in a wide variety of models representing the interactions between different species in a natural environment.

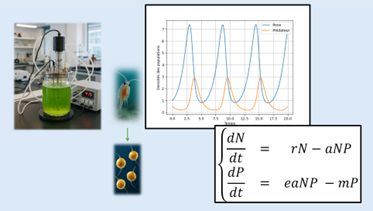

These models are based on differential equations that generalize the Lotka-Volterra model (1922-1925), initially proposed to study a system with one type of predator and one type of prey. This historic model highlighted the cycles of growth and decline in prey and predator populations, which have since been observed both in natural environments and in laboratory experiments. In the example in Figure 2, the Lotka-Volterra model can be used to reproduce the observed dynamics and estimate the biological and ecological parameters of cultivated species, such as their growth rate or mortality rate.

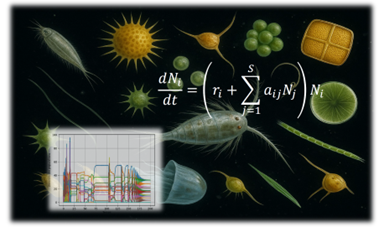

Since the last century, this model has been generalized in many different ways and, with current methods and computational resources, can be used to represent ecological networks containing a large number of interacting species, including microorganisms as well as fish, jellyfish, birds, and marine mammals. The model is enhanced by taking into account nutrients as well as the spatial distribution and movement of species.

These marine biodiversity models must also take into account natural environmental conditions, particularly the physical and chemical conditions of seawater (currents, temperature, salinity, acidity, light exposure, etc.). These model couplings pave the way for a better understanding of the interactions between biological and physical processes. For example, they now provide a better understanding of how complex movements of seawater masses structure the composition of plankton communities and how biology feeds back on the physical properties of the surrounding environment.

These complex mathematical models are then used to test hypotheses about how marine systems function and to propose experiments in the laboratory or in experimental and instrumented devices such as mesocosms. This approach has led to major advances in our understanding of these hard-to-access environments. Mathematical models are also used to establish predictive scenarios, as in the activities of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) or the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Mathematics also provides tools for better management of the marine environment and the resources it provides us with. For example, the mathematical models presented above have been adapted to better describe the impacts of fishing and improve fishing policies for sustainable exploitation. This is a major issue, as industrial fishing, along with global warming, is one of the main pressures on ocean biodiversity1 . Fishing management methods, such as setting quotas or establishing marine protected areas, are guided by mathematical models and methods. The resulting exploitation strategies have a significant impact on biodiversity, making it essential to accurately model the biology of the species concerned and their interactions with their environment.

Ocean ecosystems are highly complex environments due to the diversity of time and space scales, as well as the physical and biological processes involved. Despite this, the amount of available data is increasing thanks to the development of increasingly sophisticated observation tools (satellites, autonomous devices equipped with sensors, marine acoustics, etc.).

In addition, molecular approaches now provide rapid and accurate data on the biological and ecological properties of sampled organisms. Advancing our understanding, structuring, and exploitation of this mass of data from a wide variety of sources requires contributions from several branches of mathematics, ranging from probability theory to numerical analysis, including approaches from differential geometry and partial differential equation analysis. Currently, advances in artificial intelligence are having a considerable impact on the automation of observations and the acceleration of the numerical calculations required to solve equations in simulations. However, it is legitimate and essential to consider the environmental impact of the use of high-performance computing and artificial intelligence.

In conclusion, it is important to remember that the oceans and the biodiversity they harbor play a vital role in regulating the climate. They also provide a wide range of services, particularly in terms of living conditions and food. They are subject to numerous disturbances, including global warming, the migration of invasive species, ocean acidification, the exploitation of species consumed by humans, and others. These disturbances alter the spatial and temporal distribution of species, with increased risks of extinction. Mathematical models are therefore essential tools for understanding and better managing these ecosystems.

- 1The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that in 2021, more than 35% of species targeted by fishing are overexploited, compared to around 10% in 1974.