Maths & Oceans #1: How can whales be located in the ocean?

How can whales be located in the ocean? Can sound and distance be used? An article by Angèle Niclas, researcher and lecturer at the Applied Mathematics Laboratory at Paris 5 University1 .

- 1(MAP5 – CNRS/Université Paris Cité)

This is a question I heard during a family meal long before I approached it from a mathematical point of view. My mother-in-law, Corinne, loves whales and often goes on two-hour boat cruises that promise whale watching. But she often comes back empty-handed, complaining about the organizers who, according to her, “couldn't find a whale.”

So here's my question: in this situation, is there a method for estimating the position of a whale? I chose the example of whales today, but I could just as easily have thought of a fishing boat looking for a school of fish, or a military vessel scanning the ocean to locate a submarine. In all these cases, the principle remains the same and is based on passive sonar methods. The boat is equipped with an underwater microphone, called a hydrophone, which records the sounds propagating in the water. When the object being searched for emits a sound, that sound propagates and can be picked up by the hydrophone.

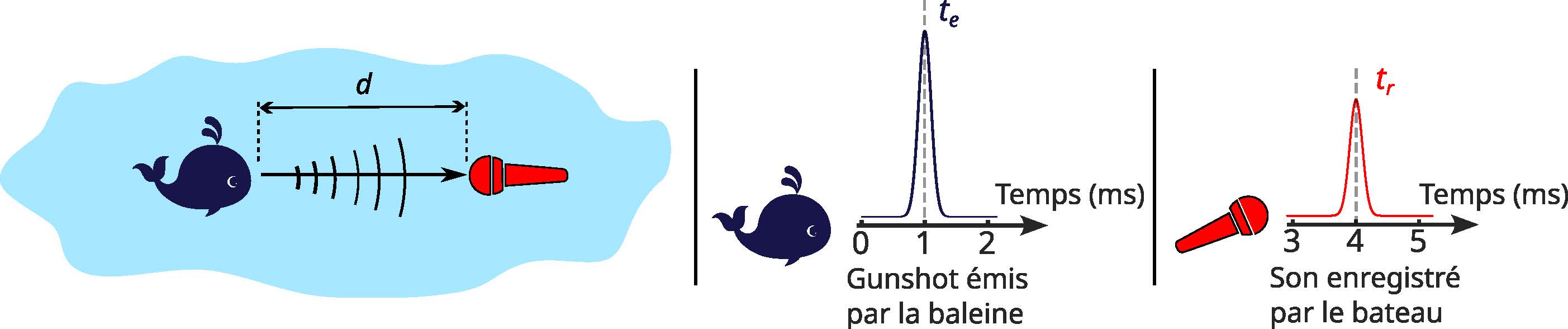

For whales, one of the most characteristic sounds is called a gunshot. This is a very clear click produced by the whale that sounds like a gunshot (you can listen to it here). This sound travels particularly well in water and is very distinct in recordings. So we have three elements: a whale emitting a gunshot, a recording of this sound from the boat, and a question: how can we use this recording to find the distance d between the boat and the whale?

The perfect situation

Let's start with the simplest case, assuming that we know exactly when the whale emitted its gunshot. Since the speed of acoustic waves in water is known (![]() ), if the sound is received by the boat at time , we can write that

), if the sound is received by the boat at time , we can write that ![]() .

.

Simple... on the surface. But two major difficulties quickly arise. You may have already identified one: how could Corinne, from the boat, know the exact moment ![]() when the whale emitted its gunshot? Without this information, we have an equation but two unknowns, which makes the problem unsolvable. The second difficulty is more subtle: the ocean is not a homogeneous environment, and sound does not propagate in a straight line

when the whale emitted its gunshot? Without this information, we have an equation but two unknowns, which makes the problem unsolvable. The second difficulty is more subtle: the ocean is not a homogeneous environment, and sound does not propagate in a straight line

Modes

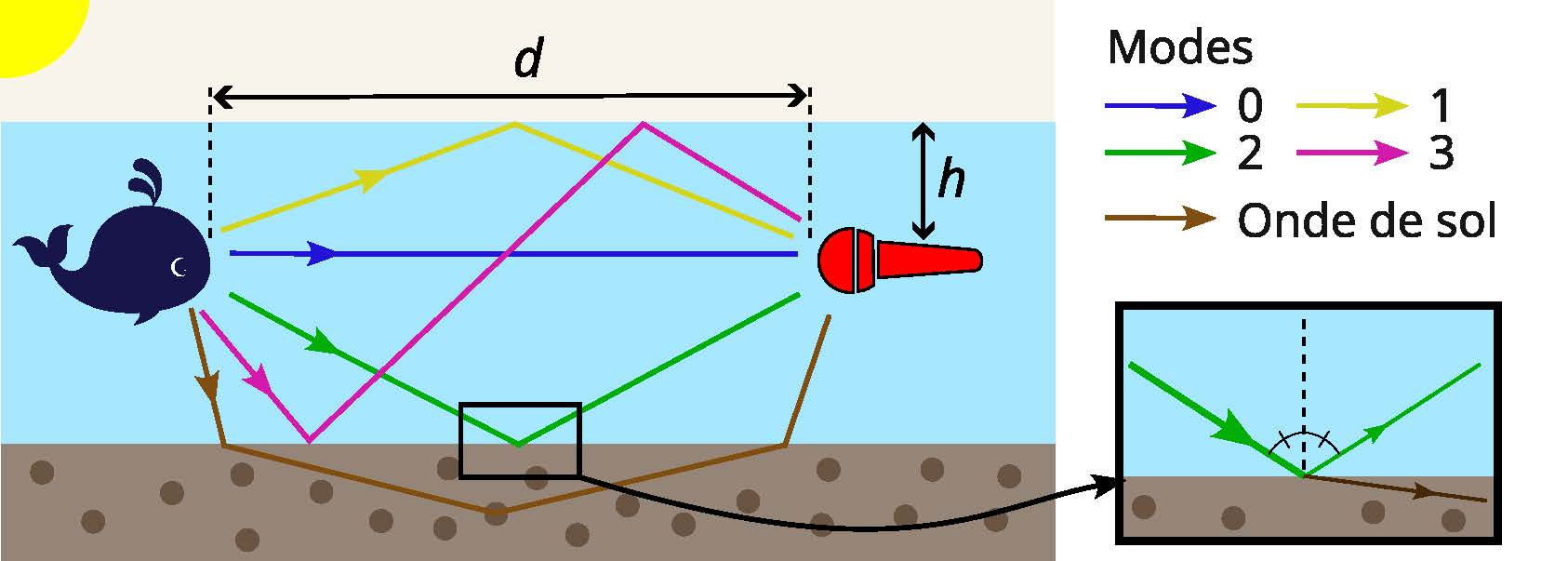

In reality, sound propagates in all directions and, when it encounters an interface (the surface of the water or the seabed), part of the acoustic energy is reflected back into the air or ground, while another part remains in the water. The directions of propagation are then given by Snell-Descartes' laws.

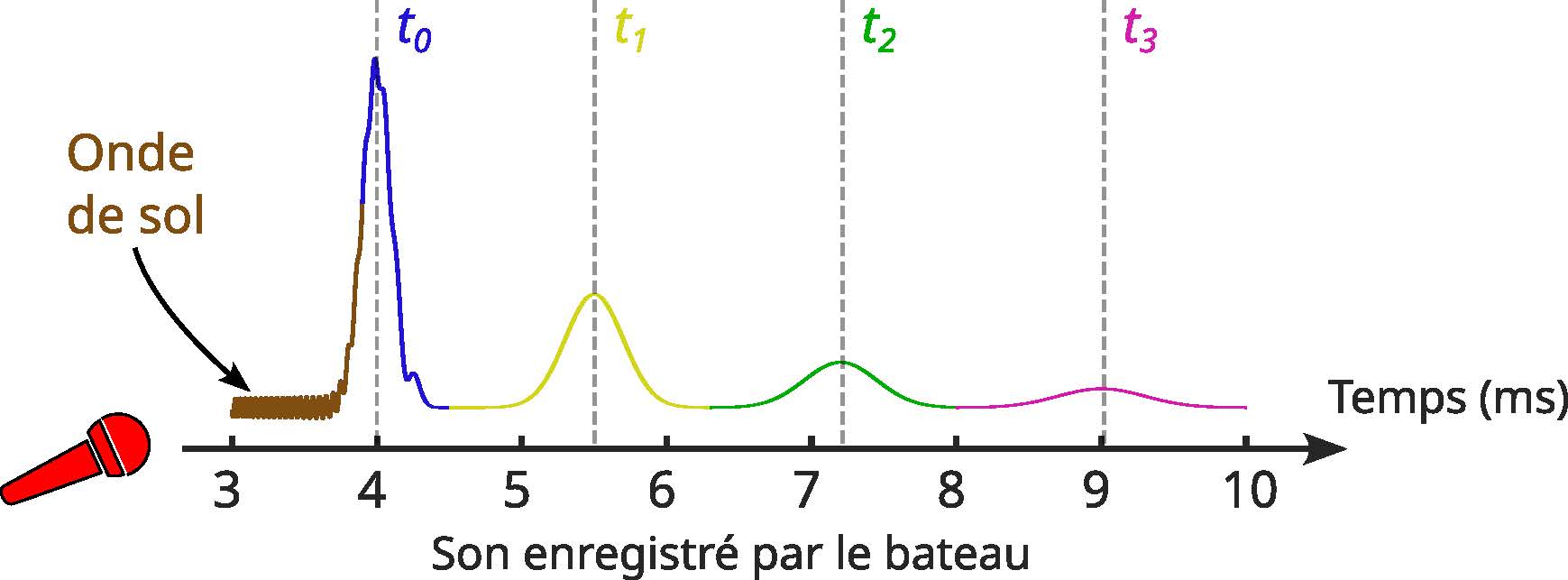

Result: to travel from the whale to the hydrophone, the wave can take several paths. These are referred to as propagation modes. The direct, straight path is called mode 0, but the sound can also bounce off the surface (mode 1), the bottom (mode 2), and then combine several successive reflections (modes 3, etc.). The received signal can thus be broken down into a theoretically infinite sum of contributions corresponding to these different modes. In practice, successive reflections dissipate energy and, beyond three or four, the signal becomes too weak to be detected.

First arrival time

Let's imagine for a moment that Corinne knows the exact time ![]() of transmission. Despite the complexity of propagation, we could simply identify the first mode received, mode 0, which arrives at time

of transmission. Despite the complexity of propagation, we could simply identify the first mode received, mode 0, which arrives at time ![]() , and apply the previous formula:

, and apply the previous formula:![]()

This approach, known as the first arrival time method, has long been used in active sonars. But even in this ideal configuration, the method faces a problem: determining the precise time ![]() is difficult, because noise interference almost always precedes the arrival of mode 0. This noise is actually caused by a particular mode, the ground wave, which propagates through the sediments on the seabed faster than through water, and reappears just before mode 0.

is difficult, because noise interference almost always precedes the arrival of mode 0. This noise is actually caused by a particular mode, the ground wave, which propagates through the sediments on the seabed faster than through water, and reappears just before mode 0.

General idea

And then, in our actual situation, the transmission time ![]() is unknown anyway. Can you see how we can get out of this? Here's a hint: use the other modes! Although I presented the complex propagation of waves in the ocean as a disadvantage, it is actually an advantage: this complexity provides us with a wealth of useful information. By measuring not only

is unknown anyway. Can you see how we can get out of this? Here's a hint: use the other modes! Although I presented the complex propagation of waves in the ocean as a disadvantage, it is actually an advantage: this complexity provides us with a wealth of useful information. By measuring not only ![]() , but also

, but also ![]() , the arrival time of mode 1, we obtain two equations with two unknowns (

, the arrival time of mode 1, we obtain two equations with two unknowns (![]() and

and ![]() ). Assuming that the whale and the microphone are

). Assuming that the whale and the microphone are ![]() meters from the surface, would you be able to find these two equations? Using our memory of geometry, we actually find that

meters from the surface, would you be able to find these two equations? Using our memory of geometry, we actually find that

then subtracting the equations that ![]() .

.

There is only one equation with one unknown left. Admittedly, it is not trivial to solve, but a calculator or computer can do it without difficulty, and if ![]() in our example and with the times from Figure 3, it can indicate that

in our example and with the times from Figure 3, it can indicate that ![]() .

.

Increasing the unknowns

But... What if Corinne doesn't know the depth of the whale? Another new unknown! All we need to do is add a third arrival time, for example ![]() . We now have three equations with three unknowns. And if the speed

. We now have three equations with three unknowns. And if the speed ![]() of the waves in the water is uncertain, we can also take into account

of the waves in the water is uncertain, we can also take into account ![]() , which gives us four equations for four unknowns. The principle is clear: the more modes we measure, the more parameters we can estimate

, which gives us four equations for four unknowns. The principle is clear: the more modes we measure, the more parameters we can estimate

Of course, the description I give here is very simplified. In reality, the signals received are not simple pulses, and the relationships linking the arrival times of the modes to the physical parameters are more complex (you can still take a look at equations 4 and 5 to get an idea). But the general idea is this: first formulate the direct problem, i.e., relate the physical parameters (![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ...) to the arrival times (

...) to the arrival times (![]() ), then solve the inverse problem, which consists of finding the parameters that best reproduce the observations, even if the equations have no exact solution.

), then solve the inverse problem, which consists of finding the parameters that best reproduce the observations, even if the equations have no exact solution.

There are many applications. In addition to giving Corinne the pleasure of seeing a whale, these non-invasive methods (since they simply listen to the sounds of the ocean) make it possible to study the movements and behavior of endangered marine species in order to better protect them. They can also be used to monitor changes in the oceans in the context of global warming: water temperature directly affects the speed of acoustic waves, and therefore the measured arrival times. As a result, recordings initially intended to detect whales or schools of fish can often also be used to extract information about local water temperature. This data is easy and inexpensive to collect: any boat equipped with a hydrophone can record thousands of such readings. Finally, as the speed of waves in the seabed also plays a role in the equations, these recordings also provide insights into the nature of the seabed, paving the way for cost-effective underwater imaging methods.

In short, locating a whale using sound is not just a matter of measuring distance: it also provides indirect information about the depth, temperature, and even the composition of the seabed. This transforms every cruise into a scientific expedition... and gives Corinne a good reason to smile when she returns.